Spirits of the Sea: Keeping Cetaceans Wild

“The time has come to view the captivity of whales and dolphin a part of our past,

not a tragic part of our future.” – Jean-Michel Cousteau

There are many animals in the sea that captivate me, but none more than the magnificent and stunning marine mammals, the whales and dolphins of our oceans. No matter how many times I come across their grace and play in the water, I find myself filled with a sense of awe and majesty for our counterparts in the sea.

Whale and dolphins, also known as cetaceans, have fascinated me throughout my life. One of my first vivid memories came as a child when my father and his team caught a group of dolphins from the Mediterranean Sea. The team wanted to study these animals and learn more about their remarkable abilities so well adapted to life underwater. From the beginning, my young mind deeply questioned the purpose of such captures. How could it be okay to take dolphins that thrived in the oceans expanse and make them prisoners in a tiny pool, separated from their families?

There was one dolphin in particular that I will never forget. Every morning before school, I would walk to the Oceanographic Museum of Monaco where the dolphins were held. One young female seemed exceptionally sad, she was not eating nor interacting with others, and was separated from the larger group for further investigation. Day after day, I’d come to her small pool and plead with my father to release her and the other dolphins. One morning, I came to greet my friend as usual, and found instead that she had died: she had rammed her head against the side of the tank, presumably taking her own life out of the agony she felt being separated from her family in the sea. This moment forever changed my perception about these intelligent, sentiment beings with whom we share our planet.

Over sixty years have passed since that first encounter with the young dolphin in Monaco. While many things have changed in the world, there are still many things that have not. Today there are still cetaceans being held in swimming pools and being asked to do circus tricks as entertainment for people and profit for amusements parks.

We have reached a point in our human evolution where people are realizing that cetaceans, including orcas and dolphins, are far too intelligent, sophisticated, and socially and behaviorally complex to be kept in concrete prisons. In captivity, they suffer from mental distress, physical illness and shorter lifespan than they would live in their natural ocean homes. Sound is their primary sense used for communication, socialization, and hunting. When confined in concrete tanks, orcas cannot fully utilize this highly evolved sense of understanding the world around them.

Fortunately, the rise of public awareness for ending cetaceans in captivity has been picking up momentum over the last few years. The release of the film Blackfish undoubtedly played an important role in bringing the conditions of orcas in captivity to the light of the public eye. Also, in what I call the communication revolution, people around the world can now connect to one another, share ideas, and come together to make their voices heard. Collectively we can change issues in our society that are no longer acceptable.

As biologists continue to study orcas and other cetaceans in the wild, they are learning how complex these animals truly are. Orcas, my favorite animals in the sea, show unique behaviors that are learned through specific orca cultures. Some populations learn to eat particular prey that requires practice and experience to capture, like the orcas in New Zealand that hunt stingrays. Other orca pods have different cultures. A pod in South America along the coast of Patagonia has learned a specific technique to capture young sea lions along the coast. By timing their body movements with the tides, they purposely beach themselves to catch prey before scurrying back into deeper water.

Most amazing to me is that orcas live in a matriarchal society – the females are in charge. Orcas are so committed to their social groups that males will usually never leave their mothers side throughout their lifetime. If their mother dies, the males often do not live much longer after her death. These are intricate social bonds established over decades of an orcas life. Orcas are the largest of the dolphin family and inhabit all oceans of the world. They rely on cultural learning and adapting to changing conditions of their ocean homes. They are not so different from us.

In captivity, it is not possible for orcas to form the same types of social relationships they have in the wild. They are often placed in tanks with orcas from different cultures communicating in different dialects. Without being able to swim, hunt, or interact with others as they would in their natural ocean home, how can we ever expect to learn anything about their true behaviors? It would be like putting a human in a prison cell and expecting to learn something about the abilities and complexity of a human being.

To truly protect and conserve marine mammals, we must recognize that captivity is not the answer. Brutal orca and dolphin drive hunts are still occurring around the world because of the demand for these animals in marine mammal aquariums. Social media is playing an instrumental role in bringing awareness about these horrific dolphin drives in places like Taiji, Japan. People from all over the world are now learning how these drive hunts herd pods of cetaceans into sheltered coves. Brokers for aquariums around the world are there first to pick the animals they want, while most of the other animals are killed for their meat or die from the distress. This is not conservation; it is cruelty.

Recently, Georgia Aquarium lost a legal battle to import 18 belugas whales that were captured from an endangered population in Russia. After the government initially denied them a permit two years ago, the aquarium sued. The courts upholding of the denial is a powerful precedent: capturing animals from endangered populations is not conservation and should not be tolerated. Instead of capturing these animals to perform circus tricks for entertainment, we should be focusing our efforts on studying wild populations, rehabilitating animals in need and teaching children that the best education comes from learning about cetaceans in the oceans.

I know it can be done. We can move beyond captivity and embrace a future with interactive educational technologies that allow people to take action and become decision-makers instead of spectators. Using engaging digital technology, people can discover through experience, learning how marine mammals communicate, hunt, socialize, and deal with conflicts and environmental challenges around them. By allowing people the opportunity to make choices, in this way, the public learns through action. We can also connect aquariums to real-time systems that monitor animals in the wild or those being rehabilitated or retired at seaside sanctuaries. I believe this is the future of aquariums, with an end to profit-driven captivity of cetaceans and other large animals.

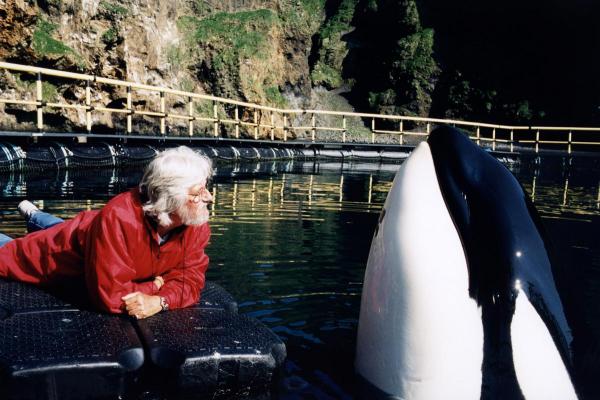

Those of us who have had the enormous privilege to see whales or dolphins in the wild know it is an experience one is likely to cherish. To see their majesty and grace is both humbling and inspiring. And if you have had the unique opportunity to share the underwater ocean realm alongside them, it becomes an experience you will never forget. In my new book, Orcas: Spirits of the Sea, I recall incredible experience I have shared with orcas and dolphins throughout my lifetime. These stories are illuminated through beautiful illustrations by Dominique Serafini.

As our societies evolve, so too must our perceptions about keeping such large, intelligent animals in unnatural confinements. How we treat orcas and other cetaceans is a reflection of how we view our natural world around us. It is time our actions reflect our understandings about the sentient beings with whom we share our planet and on which we depend for survival.

Warm regards,

Jean-Michel Cousteau

President, Ocean Futures Society

with Jaclyn Mandoske

Donate to Two Futures Society

Yes! I want to support the field work, projects and mission of Jean-Michel Cousteau and the OFS team. Make a tax-deductible donation now!

Become a Member

Yes! Sign me up for a free membership!

Connect With Us